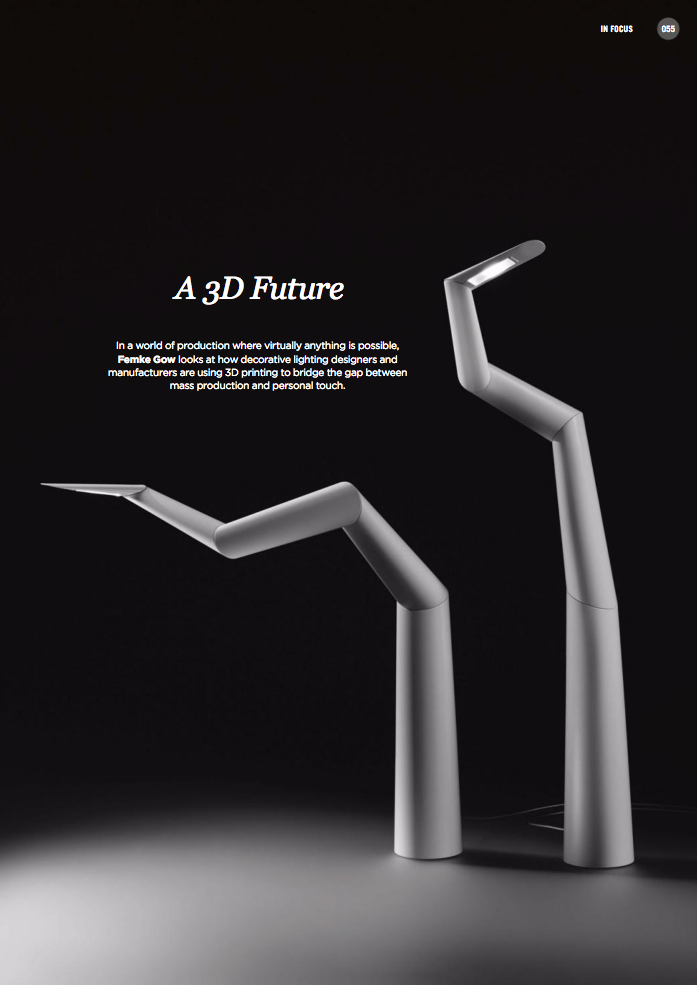

In a world of production where virtually anything is possible, Femke Gow looks at how decorative lighting designers and manufacturers are using 3D printing to bridge the gap between mass production and personal touch.

3D printing has been revolutionising the world in which manufacturers and designers create for several years now, with its production process allowing the realisation of pure imaginative form. It has seeped its way into the realms of architecture, aerospace and education, and over the past several years, penetrated the decorative lighting industry with ease. Manufacturers now see it as a logical and progressive tool that offers flexibility, while reflecting values of forward thinking technological progression that many companies hold dear to the core of their work.

HOW?

Also known as additive manufacturing, 3D printing works by adding successive layers of material under computer control to create a three dimensional object. The shape of the object printed is determined by digital model data, which is drawn digitally, and sent to the printer. There are a variety of 3D printing methods, with a process known as laser sintering standing at the forefront of popularity. A laser on the printer traces across a bed of tightly compacted powdered material (plastic, metal or otherwise), according to the 3D data fed to the machine. As the laser interacts with the surface of the powdered material, it sinters the particles to each other to form a solid. For decorative lighting manufacturers, this process enables a complete freedom of shape that is impossible to achieve with other materials in the same way.

WHO?

Amongst the many members of the decorative lighting community who have experimented with this process is German designer Ingo Maurer. Maurer uses 3D printing as an explorative technique to push the boundaries of what can be achieved. The designer has used laser sintered 3D printing to produce opaque diffusers for a number of products including Knot in 2013 and most recently Spyre in 2016. “A company like ours, which also manufactures products in limited editions, can definitely benefit from the flexibility and relatively short lead times that 3D printing allows,” says Maurer. “This technology allows designers to manufacture virtually any desired shape without incurring the prohibitive costs of having a mould manufactured. Although 3D printing is not the cheapest method, it offers more value and flexibility in investment.”

Similarly enthusiastic about the pioneering production process is Italian designer Alessandro Zambelli, who uses the process to combine innovative technology with heartfelt handicraft. Zambelli has worked with Italian technology designer and 3D printing specialists .exnovo to create Afillia and Maggiolina, two lighting collections that use polyamide laser sintering technology. Afillia is a collection of six lighting products (three table lamps and three pendant lamps), with the base in Swiss pine and a 3D printed light diffuser. Similarly, Maggiolina is composed of a handmade ceramic base with a small, rotund sintered polyamide diffuser.

The end result allows a variety of relationships with light in how the 3D printed material and interacts with light. In Zambelli’s experience, 3D printed diffusers embrace the space and create spectacular lighting effects. “Free to waver at will, the light casts fleeting shadows, then beams into unexpected focus, forming compact halos, round and bright,” said Zambelli. “This is energy in fluid form in the no-man’s land between stuff and shape, air and light.”

As well as laser sintering, there are other methods used within the lighting industry to develop unique parts and products of decorative lamps. British lighting manufacturer Plumen has used the Fusion Deposit Modelling process, in collaboration with Milan-based 3D printing design studio Formaliz3d. This is the most cost-efficient process and works by extruding a filament to build the model. Formaliz3d adapted its own distinct Rumbles shade to marry with the shape of Plumen’s Baby and 002 lamps in an elegant shade. Made of a material called PLA, a biodegradable plastic made from cornstarch or sugarcane, the shade features punctured edges to produce a visually intriguing lighting effect.

Plumen Co-founder and Creative Director Nicolas Roope commented: “We approached Formaliz3d and asked if we could collaborate to adapt the Rumbles form for specific use with Plumen lamps. Seven days later, we had a sample in our hands. After one round of amendments, we had the finished Plumen edition of the Kayan shade and it was beautiful.”

Roope explains that although unit costs are higher than mass produced products, there are literally no pre-production costs and the scope is greater for forms as the constraints of moulding materials do not exist.

“A lighter design process and less preproduction made the whole thing a lot faster and more cost effective. This was great for small runs, and allows for many more forms to be created. In many cases, it also does away with the need to join up sections as they are simply fused together in the print.”

Another way manufacturers use 3D printing is in the product development stage. Astro’s Head of Product Development Stuart Wells commented: “With 3D printing we can quickly assess form, fit and in some cases function, so we use the technology to prove a concept. This helps shorten lead times for developing a product from initial idea to production.”

WHY?

The reasons that manufacturers opt for 3D printing seem to be unanimous; Wells also argues for its cost and manufacturing advantages, commenting: “3D printing has been used to create shades for table and floor lights, and as the technology grows and printing with metallic material become readily available, more decorative components could be made in this way,” he says. Repeatability and no tooling costs are things all industries could benefit from, however material and equipment costs must come down and print speeds increase.

For Roope, 3D printing complements Plumen’s process of the unique Plumen light source being the starting point for every project. “We’re specifically looking for shades to show off and enhance the qualities of form and light that each of our models emit.”

Kayan’s 3D printed shade is perforated, letting light through and also allowing room for the form of the Plumen lamp to be appreciated. From further back, the material colour becomes more prominent and the form, especially when used in a series, has a strong architectural effect.

In further support of 3D printing, the translucency of sintered polyamide lends itself well to decorative lighting products. Maurer says: “The light generated from halogen and LED sources works well and harmonises with this material. The designer can decide the thickness of the print out, and while there is a limited range, at least some choice is available. The homogenous surface of the polyamide blends light well and diffuses it in a warm and pleasant tone. The luminosity of the fixtures is not compromised as the material is translucent and allows most of the light to filter through.”

WHY NOT?

Despite the attractiveness of this innovative process in its ability to combat issues of fluidity and creative freedom in production, it still comes with its drawbacks as an emerging material.

Zambelli deems a good product designer as one who takes the time to discover the secrets of a material and use the right material for the right project, and 3D printing is not always the best solution.

With the most frequently 3D printed material being plastic, Zambelli still sees this as a poor material, making it difficult to convey real value. “This is why I combine 3D printed plastics with wood or hand-made ceramics because people really relate to those materials. The combination gives the product value, and I think without it, they would be cold.”

With this in mind, Zambelli approaches new projects with a “Can I 3D print it?” attitude, and wants to experiment with the process applied to other materials such as metals and ceramics, as Plumen have.

Another aspect of 3D printed materials that manufacturers feel needs some attention is the surface of the end result. Maurer targets the limitation of precise and exact tolerances of surface treatments as the main area of improvement of this process. “The surface development would need to be enhanced in order to achieve a smooth finish, thus eliminating the extra time needed to prepare the surface area so that it can be lacquered,” says Maurer. “I know it is only a matter of time before this develops in the 3D printing industry.”

WHAT NEXT?

With regards to how the decorative lighting community sees the future of 3D printing developing in its industry, there are some exciting things to look out for. Interested in the blended version of the future where some parts of products are mass produced and some are customised, Plumen is working along the lines of mechanical models that come straight out of the printer and move. “Watch this Plumen space!” says Roope. “The potential of 3D printing is enormous. Mass manufacture is necessary for many things and will continue to define many of the products we consume. But in homeware and lighting, where design and self expression play such a large part in consumer choice, the flexibility and personality that 3D printing offers will eventually redefine this category.”

In line with this idea is Maurer’s vision for the future of 3D printing as he sees it creating a platform for innovation. “If well utilised, this technology can help designers produce original designs and superior products. The technological leap with this material and technique into other unknown materials is an open frontier for us and for all designers to explore.”

Astro’s Wells supported these positive prospects in recognising the ability of 3D printing to increase speed to market: “The ability to design, engineer and create all under one roof in an office environment greatly reduces the time to bring a product into the market place. As 3D printing moves into more robust materials, samples for testing in different environments become more useful. This will further assist the reduction of bringing a luminaire to market.”

In conclusion, the common consensus draws on the flexibility and creative allowance that 3D printing offers. The result is a direct translation of what a designer is capable of imagining, rendering the process as close to the heart of their creations as possible. Given its minor drawbacks, these seem to be parts of the process that will develop with technology and time, gradually making way for flawless production and a great leap into the limitless unknown.